+

- 06-02-2022

- Grégoire Bideau

- Steven Tallec

Recherche

Audiovisuel

Recherche

Audiovisuel

Algorithmic panic: European contents on the Netflix homepage

20 bots watched Netflix every day for 8 days, here is what their homepages tell us about the prominence of European works on the platform.

Is Netflix doing enough to promote European contents to its European users? If a user never watches any European films or TV series, will European works simply disappear from the homepage? Doesn’t algorithmic personalisation mean that filter bubbles will trap the user in his or her own tastes?

For the past couple of years, these questions have been repeatedly asked by a number of stakeholders in the European audiovisual industry, from regulators to producers, to government officials and analysts, bearing witness to a certain scepticism toward Netflix’s recommender system. More than a decade since Pariser’s blockbuster book1 was published, it is still often taken for granted that all recommender systems create filter bubbles and, in doing so, constitute a threat to European contents’ prominence online. But are fears of disappearance from the homepage justified or are they unfounded? Interestingly, no quantitative study has ever been carried out to answer that question and, despite a real lack of data pertaining to prominence on VOD services, the perceived threat that algorithms pose is enough to send professionals, regulators and decision-makers alike into what we might call an "algorithmic panic," prompting them to take steps to solve a "problem" that has not even been confirmed using scientific methods.

Methodology

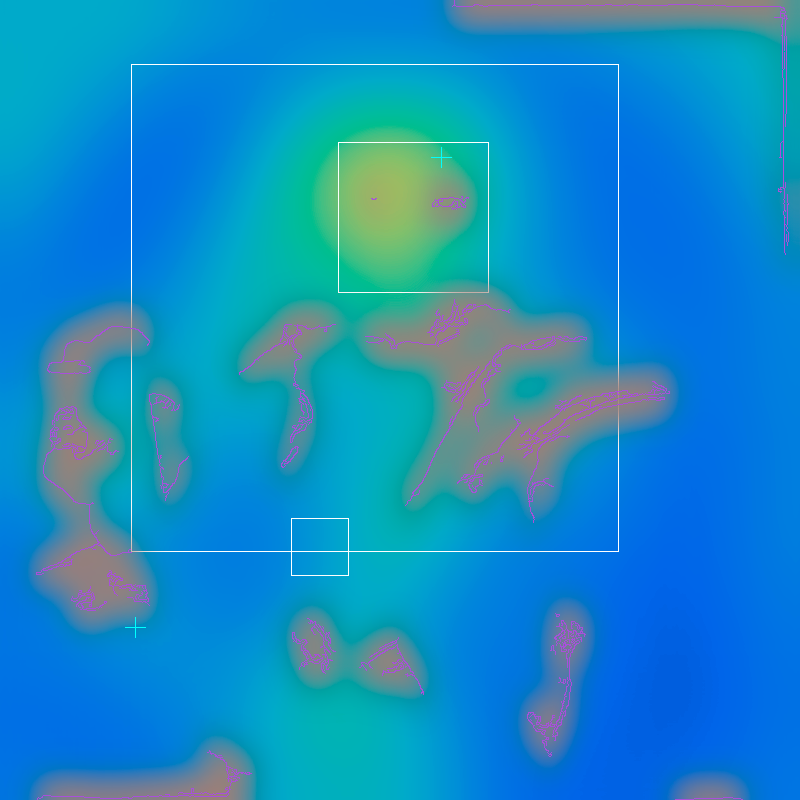

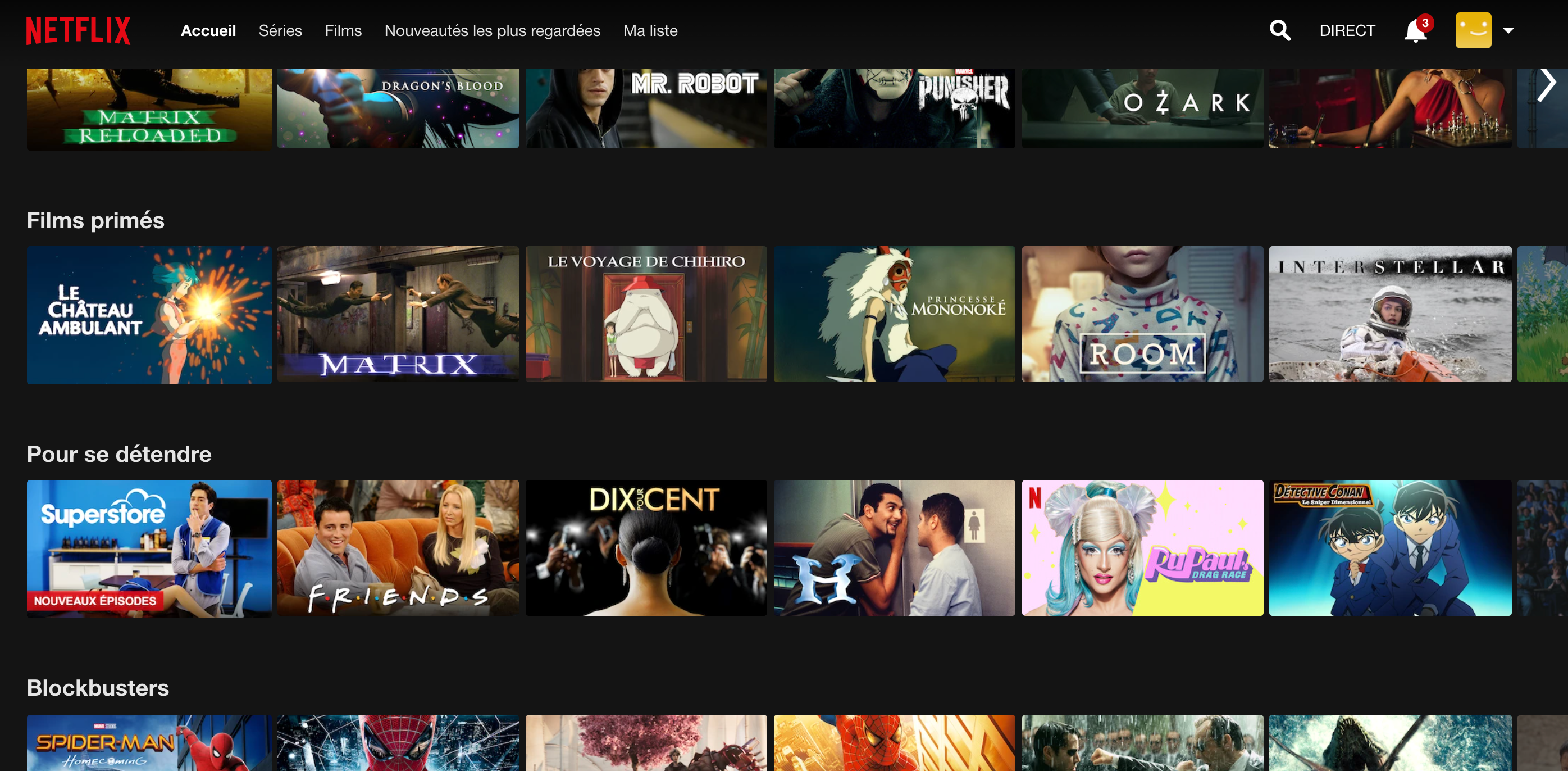

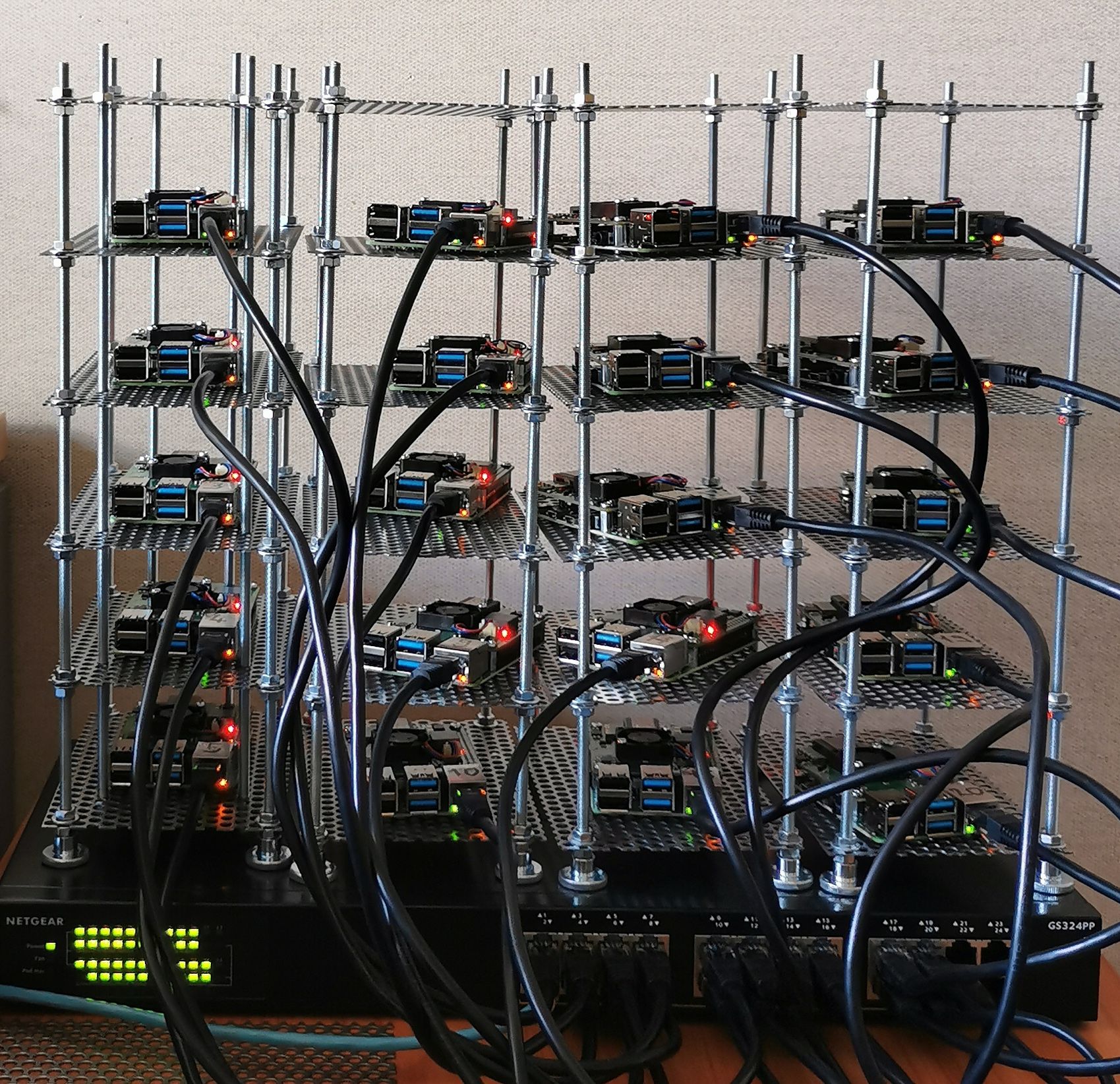

As part of our ongoing effort to understand the mechanisms that underpin content prominence online, we have developed a robust methodology2 that allows us to study the effects of viewing behaviour on the placement of content on the Netflix homepage. We employ it here to survey the placement of European works with regard to past viewing behaviour. To put it briefly, our method consists of 20 Raspberry Pi’s (tiny single-board computers), each provided with a different newly created Netflix account, watching 3 hours of content and collecting the position of every title on the homepage each day. The bots’ actions are pre-programmed and there is no human intervention during the whole process.

For the purposes of this experiment, 10 bots watched only European contents and the 10 remaining bots watched non-European contents, films and TV series alike. Before the start of the experiment, each bot was given a list of titles to watch, selected at random from the whole Netflix catalogue with the only criteria being their European3 nature. Our goal in setting up this experiment was to remove as many biases as possible. The fact that the creation of a new profile, the parsing of the homepage and the viewing of contents are all happening simultaneously for all bots ensures that our results are not skewed by time-based discrepancies. What’s more, the random selection of titles eliminates selection bias, although it does result in extremely atypical viewing patterns from our bots. Finally, all bots are housed in the same "cluster" (see photo below), meaning that they share the same IP address (in Paris), thus eliminating any location bias.

The experiment lasted for 8 days, which we felt was an appropriate length of time from which to gain valuable insights. As mentioned above, each bot watched 3 hours of content each day, from 6pm to 9pm, and from October 12th to October 19th 2021.

Results

— Number of thumbnails promoting European contents on the homepages of bots that watched only European contents

— Number of thumbnails promoting European contents on the homepages of bots that watched only non-European contents

The graphs above show the daily number of thumbnails advertising European titles on each bot’s homepage. Note that the two sudden drops on the second graph correspond to significantly smaller homepages (3 and 2 rows respectively), a rare occurrence due not to a bug in our code but to as-of-yet unexplained behaviour displayed by the recommender system.4

A cursory glance at both graphs reveals a slight upward trend for bots that watched only European contents, and a corresponding downward trend for those bots that watched only non-European contents. Given the extreme nature of both sets of bots’ viewing habits, the scale and speed of the evolution towards more or fewer European contents on the homepage seem moderate. The algorithm does respond, in most cases, to a user’s attitude toward European contents: watching only European works on Netflix tends to result in an increase in the number of European thumbnails on the homepage and vice-versa.

— Number of thumbnails promoting European contents on the top 10 rows of the homepage (billboard included), for bots that watched only European contents

— Number of thumbnails promoting European contents on the top 10 rows of the homepage (billboard included), for bots that watched only non-European contents

When it comes to prominence on the homepage itself, similar patterns emerge. For the two graphs above, we chose to look at only the top 10 rows on the homepage.5 As with the homepage as a whole, bots that have watched only European contents tend to see an increase in the number of thumbnails promoting European works within the top 10 rows. With a few exceptions, the inverse is also true. Again, for those bots that have not watched any European contents, we can clearly see that they have not disappeared from the top of the homepage. It is important to also bear in mind that the top 10 rows include non-recommended rows such as "Continue watching for..." and the country’s "Top 10 in...", which feature titles that have not been selected by the recommender system.

— Average number of distinct European titles on the homepage

Shifting our focus from the number of thumbnails to the number of different titles on the homepage6 reveals that the upward trend caused by watching European content does not coincide with a corresponding downward trend when the inverse is true. For bots that have watched only European works, the average number of European titles on the homepage gradually increases, reaching 350 on the last day of the experiment. This number remains more or less steady however for our “non-European” bots.

— Number of thumbnails per country of production, all homepages combined, descending order

No sheet data, sorry

As an aside, and moving away from a strictly European viewpoint, we looked at the countries whose productions were featured the most on the homepage7 and, rather surprisingly, the top 5 are the same for both categories of bots. France, where the experiment took place, has the second highest overall number of thumbnails promoting French productions,8 albeit far behind the US, the leader by a factor of around four. Our methodology does not allow us to determine whether this is the result of high demand for French content or an editorial choice on Netflix’s part. Japanese productions occupy fourth place, probably due in no small part to the popularity of Japanese anime on the platform. Mexico is a rather unexpected entry at seventh place.

Over the course of our 8-day experiment, 92% of all European titles available on Netflix have appeared at least once on one of the bots’ homepages. What this means is that the vast majority of European works on Netflix have been "pushed," in varying degrees, to the homepage at least once. Some have been featured multiple times in the top rows, others only once in the bottom rows, but only very few have never appeared on the homepage at all. The scale and speed at which the homepage evolves in response to a user’s viewing behaviour is such that, overall, there does not seem to be many "dormant" titles buried deep within the catalogue and never surfacing to users’ screens.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that European works do not suddenly disappear from the homepage, even when a user only watches non-European titles on Netflix. It would seem then that the fear of “invisibility by way of the algorithm”, expressed by many European professionals and regulators, is unfounded. Objectively, there appears to be no cause for concern, and so we might begin to examine the reasons for such a widespread distrust of Netflix’s recommender system. Why then were these fears relayed by the media and some professionals?

We put forward two hypotheses, each warranting further discussion:

- A lack of confidence in the attractiveness of European works. If all contents were to compete for attention on an equal footing, what would make European contents more attractive than others? After decades of US hegemony at the box office and in TV ratings, European professionals tend to assume that audiences will always favour foreign over local content. When applied to recommender systems which, we are told, personalise recommendations based on past viewing behaviour, this line of thinking can only come to a rather defeatist conclusion: if nothing is done, our unattractive European works will simply never be recommended. Hopefully, the recent proliferation of European success stories on streaming services will start to chip away at that idea, and European stakeholders will begin to view recommender systems in another light.

- The fear of a loss of cultural sovereignty. European lawmakers like to ensure a minimum degree of exposure to European works on every media format, and they do so for different, more or less explicit reasons: to promote so-called cultural diversity, to protect otherwise endangered sectors of industry and to safeguard against perceived American cultural imperialism. All of these endeavours require a certain level of control, typically exerted through the imposition of financing obligations and broadcast quotas. However, the necessary relinquishing of control that recommender systems entail makes regulation pertaining to content prominence inadequate and difficult to enforce. Viewed in this light, the fear of seeing European works disappear from the homepage of a service like Netflix stems not from an actual, witnessed scenario but from what could in theory happen when control over prominence is transferred to an unknown, impersonal entity: the algorithm. Left to its own devices, it is presumed that the algorithm will act against the European Union’s best interests, leaving no room on the homepage for local content. Moreover, the fact that the algorithm was built in the US, Europe’s long-time "cultural aggressor," only serves to reinforce the prejudice.

Whatever the reason for Europeans’ scepticism toward cultural recommender systems, there is a pressing need for actionable data from which to confirm or alleviate those concerns. Our methodology aims to do just that, and has shown itself to be reliable enough to provide quantitative insights into content prominence in the context of an algorithmically generated homepage. We will continue to put it to use in future experiments, where we will explore other variables such as release dates, languages and genres.

Notes

- ↑

Pariser, E. (2011) The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding from You. London: Viking/Penguin Press.

- ↑

For a detailed explanation of the methodology, please refer to the document "A method for measuring con- tent prominence on Netflix", available online on pcen.fr or as a pdf on request.

- ↑

As per the signatories of the Television Without Borders agreement and determined by metadata collected from IMDb.

- ↑

One can surmise that the randomness in the bot’s selection of titles confounds the algorithm somewhat, and renders it incapable of displaying a full page of recommendations, although this is only an unverified hypothesis.

- ↑

An arbitrary choice, which may need some fine-tuning in the future. For reference, on average, the top 10 rows contain between 250 and 300 thumbnails.

- ↑

Bear in mind that each title may—and often does—appear multiple times on the homepage, in different thumbnails.

- ↑

Again, using IMDb as our source.

- ↑

No distinction was made here between co-productions with other countries and single-country productions.